Shoulder Instability

Education

Shoulder Instability

Shoulder instability occurs when the structures that keep the shoulder joint in place are stretched, weakened, or torn, allowing the ball of the upper arm bone (humeral head) to move excessively or slip out of the socket (glenoid). This can result in pain, apprehension, or repeated dislocations.

It is a common condition in young athletes, especially those involved in contact sports or overhead activities, but can also affect older adults following a traumatic shoulder injury.

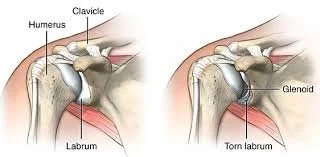

Shoulder Anatomy

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the body, relying on a balance of static and dynamic stabilizers for stability:

Static stabilizers: Labrum, capsule, and ligaments (especially the inferior glenohumeral ligament)

Dynamic stabilizers: Rotator cuff and periscapular muscles

When these stabilizers are compromised, the shoulder may sublux (partially slip out) or dislocate completely.

Types of Shoulder Instability

Anterior Instability: The most common type, where the shoulder slips forward—typically caused by a traumatic event.

Posterior Instability: Less common; often seen in weightlifters or athletes with repetitive posterior stress.

Multidirectional Instability (MDI): Instability in more than one direction, often associated with generalized ligamentous laxity.

Causes and Risk Factors

Traumatic dislocation: A fall or direct blow can tear the labrum and stretch ligaments.

Repetitive overhead motion: Common in throwing athletes or swimmers.

Genetic ligamentous laxity: “Double-jointed” individuals are more prone to MDI.

Prior shoulder dislocations: Increases the risk of recurrent instability.

Symptoms

Patients may experience:

A sensation of the shoulder "slipping" out of place

Recurrent dislocations or subluxations

Pain with overhead or throwing motions

Apprehension or fear with certain movements

Weakness or reduced performance in sports or daily activities

Diagnosis

Diagnosis involves:

Physical examination: Apprehension test, relocation test, and load-and-shift test

X-rays: To assess for bone loss or Hill-Sachs/Bankart lesions

MRI with contrast (MR arthrogram): To evaluate labral tears, capsular laxity, or rotator cuff pathology

CT scan: May be used to assess glenoid bone loss in recurrent cases

Treatment Options

Management depends on the type, severity, activity level, and presence of structural damage.

Non-Surgical Management:

Physical therapy focused on strengthening the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers

Activity modification, especially for overhead or contact sports

Bracing or taping in certain athletic situations

Often the first line of treatment, especially in non-traumatic or first-time dislocations without bone loss.

Surgical Management:

Arthroscopic Bankart Repair: Reattachment of the torn labrum and tightening of the capsule—common for anterior instability.

Latarjet Procedure: Bone transfer procedure used when there is significant glenoid bone loss.

Capsular Shift or Plication: Tightens a loose capsule, often used in MDI.

Posterior Labral Repair: For patients with posterior instability due to labral tearing.

Surgery is typically indicated for recurrent instability, high-risk athletes, or those with significant structural damage.

Recovery and Outlook

Sling immobilization for 3–6 weeks postoperatively

Gradual rehabilitation focusing on range of motion, then strength and control

Return to sports typically at 4–6 months, depending on procedure and sport demands

Most patients regain full function, especially when surgery is appropriately matched to the type of instability and activity level.

Conclusion

Shoulder instability can lead to recurrent dislocations, pain, and impaired performance if not properly managed. With modern rehabilitation techniques and surgical options, most patients—whether weekend warriors or elite athletes—can return to their desired level of activity.

If you're experiencing shoulder instability or have had a dislocation, early evaluation is key to preventing long-term damage and optimizing outcomes.